Understanding Gradient Clipping (and How It Can Fix Exploding Gradients Problem)

Gradient clipping solves one of the biggest problems that we have while calculating gradients in backpropagation for a neural network.

You see, in a backward pass, we calculate the gradients of all weights and biases in order to converge our cost function. These gradients, and the way they are calculated, are the secret behind the success of artificial neural networks in every domain.

But every good thing comes with some sort of caveat.

Gradients tend to encapsulate information they collect from the data, which also includes long-range dependencies in large text or multidimensional data. So, while calculating complex data, things can go south really quickly, and you’ll blow your next million-dollar model in the process.

Luckily, you can solve it before it occurs (with gradient clipping). Let’s first look at the problem in depth.

By the end of this article, you’ll know:

- What is gradient clipping and how does it occur?

- Types of clipping techniques

- How to implement it in Tensorflow and PyTorch

- Additional research for you to read

Common problems with backpropagation

The backpropagation algorithm is the heart of all modern-day machine learning applications, and it’s ingrained more deeply than you think.

Backpropagation calculates the gradients of the cost function w.r.t. the weights and biases in the network.

It tells you about all the changes you need to make to your weights to minimize the cost function (it’s actually -1*∇ to see the steepest decrease, and +∇ would give you the steepest increase in the cost function).

Vanishing gradients

What about deeper networks, like Deep Recurrent Networks?

The translation of the effect of a change in cost function (C) to the weight in an initial layer, or the norm of the gradient, becomes so small due to increased model complexity with more hidden units that it becomes zero after a certain point. This is what we call vanishing gradients.

This hampers the learning of the model. The weights can no longer contribute to the reduction in cost function (C) and go unchanged, affecting the network in the forward pass and eventually stalling the model.

Exploding gradients

On the other hand, the exploding gradient problem refers to a large increase in the norm of the gradient during training.

Such events are caused by an explosion of long-term components, which can grow exponentially more than short-term ones. This results in an unstable network that, at best, cannot learn from the training data, making the gradient descent step impossible to execute.

Deep dive into exploding gradients problem

For calculating gradients in Deep Recurrent Networks we use an approach called backpropagation through time (BPTT), where the recurrent model is represented as a deep multi-layer one (with an unbounded number of layers), and backpropagation is applied to the unrolled model.

In other words, it’s backpropagation on an unrolled RNN.

Unrolling recurrent neural networks in time by creating a copy of the model for each time step:

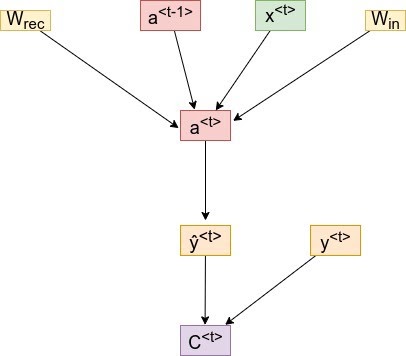

We denote by a<t> the hidden state of the network at time t, by x<t> the input and ŷ<t> the output of the network at time t, and by C<t> the error obtained from the output at time t.

Let’s work through some equations and see the root where it all starts.

We will diverge from classical BPTT equations at this point and rewrite the gradients in order to better highlight the exploding gradients problem.

These equations were obtained by writing the gradients in sum-of-products form.

We will also break down our flow into two parts:

- Forward Pass

- Backward Pass

Forward Pass

First, let’s check what intermediate activations of neurons at timestep <t> will look like:

W_rec represents the recurrent matrix that will carry the translative effect of previous timesteps.

W_in is the matrix that gets multiplied by the current timestep data and b represents bias.

An intermediate output at timestep <t> will look something like:

Note that here “σ” represents any activation function of your choice. Popular picks include sigmoid, tanh, and ReLU.

Using the predicted and ground-truth values, we can calculate the cost function of the entire network by summing over individual Cost functions for every timestep <t>.

Now that we have the general equations for the calculation of the cost function, let’s do a backward propagation and see how gradients get calculated.

Backward Pass

In order to acquire the gradients from all timesteps, we again do a summation of all intermediate gradients at timestep <t> and then the gradients are averaged over all training examples.

So, we have to calculate the intermediate cost function (C) at any timestep <t> using the chain rule of derivatives.

Let’s look at the dependency graph to identify the chain of derivatives:

For a timestep <3>, our cost function will look something like:

Note: We’ve only mentioned the derivative w.r.t to W, which represents all the weights and bias matrices we’re trying to optimize.

As you can see above, we get the activation a<3>, which will depend on a<2>, and so on until the first layer’s activation is not calculated.

Hence, the dependency will go something like:

a<t> → a<t-1> → a<t-2> → …. → a<1>

So if we take the derivative to W, we can’t simply treat a<3> as a constant.

We need to apply the chain rule again. Finally, our equation will look something like this:

We sum up the contributions of each time step to the gradient.

In other words, because W is used in every step up to the output we care about, we need to backpropagate gradients from t = 3 through the network all the way to t = 0.

So, in order to calculate activation for a timestep <t>, we need all the activations from previous timesteps.

Note that ∂a<T>/∂a<k> is a chain rule in itself! For example:

Also note that because we are taking the derivative of a vector function with respect to a vector, the result is a matrix (called the Jacobian matrix) whose elements are all the pointwise derivatives.

We can rewrite the above gradient in Eq. 1.6:

This represents a Jacobian Matrix whose value is calculated using Frobenius or 2-norm.

To understand this phenomenon, we need to look at the form of each temporal component, and in particular at the matrix factors ∂a<t>/ ∂a<k> (Eq:1.6,1.9) that take the form of a product of (t − k) Jacobian matrices.

In the same way that a product of (t − k) real numbers can shrink to zero or explode to infinity, so can this product of matrices (along with some direction v).

Hence, we get the condition of Exploding Gradients due to this temporal component.

How to identify and catch exploding gradients?

The identification of these gradient problems is hard to comprehend before the training process is even started.

When your network is a deep recurrent one, you have to:

- constantly monitor the logs,

- record sudden jumps in the cost function

This will tell you whether these jumps are frequent and if the norm of the gradient is increasing exponentially.

The best way to do this is by monitoring logs on a visualization dashboard.

We’ll utilize neptune.ai’s visualization and dashboarding of the logs to monitor the loss and other metrics which will help in the identification of Exploding gradients. You can head over to the detailed documentation to set up your dashboard.

Disclaimer

Please note that this article references a deprecated version of Neptune.

For information on the latest version with improved features and functionality, please visit our website.

Fix exploding gradients through gradient clipping

There are a couple of techniques that focus on exploring gradients problem.

One common approach is L2 regularization, which applies “weight decay” to the cost function of the network.

The regularization parameter gets bigger, the weights get smaller, effectively making them less useful and, as a result, making the model more linear.

However, we’ll focus on a technique that’s far superior in terms of gaining results and ease of implementation – Gradient Clipping.

What is gradient clipping?

Gradient clipping is a method where the error derivative is changed or clipped to a threshold during backward propagation through the network, and the clipped gradients are used to update the weights.

By rescaling the error derivative, the updates to the weights will also be rescaled, dramatically decreasing the likelihood of an overflow or underflow.

Gradient Clipping is implemented in two variants:

- Clipping-by-value

- Clipping-by-norm

Gradient clipping-by-value

Gradient clipping is implemented in two variants:

- Clipping-by-value

- Clipping-by-norm

Gradient clipping-by-value

The idea behind clipping-by-value is simple. We define a minimum and a maximum clip value.

If a gradient exceeds some threshold value, we clip that gradient to the threshold. If the gradient is less than the lower limit, then we clip that too, to the lower limit of the threshold.

The algorithm is as follows:

g ← ∂C/∂W

if ‖g‖ ≥ max_threshold or ‖g‖ ≤ min_threshold then

g ← threshold (accordingly)

end if

where max_threshold and min_threshold are the boundary values, and between them lies a range of values that gradients can take. g, here is the gradient, and ‖g‖ is the norm of g.

Gradient clipping-by-norm

The idea behind clipping-by-norm is similar to clipping-by-value. The difference is that we clip the gradients by multiplying the unit vector of the gradients with the threshold.

The algorithm is as follows:

g ← ∂C/∂W

if ‖g‖ ≥ threshold then

g ← threshold * g/‖g‖

end if

where the threshold is a hyperparameter, g is the gradient, and ‖g‖ is the norm of g. Since g/‖g‖ is a unit vector, after rescaling, the new g will have a norm equal to the threshold. Note that if ‖g‖ < c, then we don’t need to do anything.

Gradient clipping ensures the gradient vector g has a norm at most equal to the threshold.

This helps gradient descent to have reasonable behavior even if the loss landscape of the model is irregular, most likely a cliff.

Gradient clipping in deep learning frameworks

Now we know why exploding gradients occur and how gradient clipping can resolve it.

We also saw two different methods by virtue of which you can apply clipping to your deep neural network.

Let’s see an implementation of both gradient clipping algorithms in major machine learning frameworks: Keras, and PyTorch.

Gradient clipping in Keras

We’ll employ the MNIST dataset, which is open-source digit classification data meant for image classification.

Before we jump into code, please install the following libraries in a virtual environment:

$ conda create -n gradient_clipping python=3.10 -y

$ conda activate gradient_clipping

$ pip install tensorflow pytorch neptune python-dotenv

First, let’s import the necessary modules and libraries:

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow.keras import layers, models

from tensorflow.keras.datasets import mnist

import neptune # pip install neptune

import os

Next, create a file named .env in your working directory and paste the following contents:

NEPTUNE_PROJECT_NAME="community/gradient-clipping" # CHANGE TO YOURS

NEPTUNE_API_TOKEN="YOUR_TOKEN_FROM_NEPTUNE"

This will enable you to load these variables into your notebook or script when initializing a Neptune run object, like below:

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv()

project_name = os.getenv("NEPTUNE_PROJECT_NAME")

api_token = os.getenv("NEPTUNE_API_TOKEN")

# Neptune setup

run = neptune.init_run(project=project_name, api_token=api_token)

The run object helps us log training details and model metadata to your Neptune project dashboard.

Now, let’s load and pre-process the MNIST dataset:

(x_train, y_train), (x_test, y_test) = mnist.load_data()

x_train, x_test = x_train / 255.0, x_test / 255.0

Now, we build a simple sequential model:

model = models.Sequential(

[

layers.Flatten(input_shape=(28, 28)),

layers.Dense(128, activation="relu"),

layers.Dense(10, activation="softmax"),

]

)

Now, we come to the critical part: specifying how we perform the clipping. Fortunately, we can do this in a single line of code while defining the optimizer to use:

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001, clipnorm=1.0) # Clip by norm

# optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001, clipvalue=0.5) # Clip by value

The above snippet shows both clipping by norm and clipping by value (commented) versions of the code. The rest of the code involves training the model:

model.compile(

optimizer=optimizer, loss="sparse_categorical_crossentropy", metrics=["accuracy"]

)

# Log parameters

run["parameters"] = {

"learning_rate": model.optimizer.learning_rate,

"clip_norm": model.optimizer.clipnorm,

# "clip_value": model.optimizer.clipvalue, # Uncomment if using clipvalue instead of clipnorm

}

# Train the model

history = model.fit(x_train, y_train, epochs=5, validation_split=0.2, batch_size=32)

And capturing the training details from the history object with Neptune:

for epoch, (loss, acc, val_loss, val_acc) in enumerate(

zip(

history.history["loss"],

history.history["accuracy"],

history.history["val_loss"],

history.history["val_accuracy"],

),

1,

):

run["training/train/loss"].append(loss)

run["training/train/accuracy"].append(acc)

run["training/validation/loss"].append(val_loss)

run["training/validation/accuracy"].append(val_acc)

run.stop()

The above lines will log training and validation loss and accuracy to the higher-level training directory.

Once the run finishes, you can visit the Runs tab of your Neptune dashboard to see the training process visualized, like below:

You can capture more information and metadata if you use the Neptune-Keras integration. Instead of using a run object and logging metrics manually with the append() method, you can use a single class and pass it as a callback to the fit method of the Keras model object:

from neptune.integrations.tensorflow_keras import NeptuneCallback

neptune_callback = NeptuneCallback(run=run)

model.fit(

...,

callbacks=[neptune_callback],

)

The training details will be captured automatically.

PyTorch

In this section of implementation with PyTorch, we’ll load data again, but now with the PyTorch DataLoader class, and use the pythonic syntax to calculate gradients and clip them using the two methods we studied.

import os

import argparse

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

import torch.optim as optim

import torchvision

from torch.optim.lr_scheduler import StepLR

import neptune

run = neptune.init_run(project=project_name,

api_token=api_token)

Now, let’s declare some hyperparameters and the DataLoader class in PyTorch.

# Hyperparameters

n_epochs = 2

batch_size_train = 64

batch_size_test = 1000

learning_rate = 0.01

momentum = 0.5

log_interval = 10

random_seed = 1

torch.backends.cudnn.enabled = False

torch.manual_seed(random_seed)

# Device configuration

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

sequence_length = 28

input_size = 28

hidden_size = 128

num_layers = 2

num_classes = 10

batch_size = 100

num_epochs = 2

learning_rate = 0.01

os.makedirs("files", exist_ok=True)

train_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

torchvision.datasets.MNIST(

"files/",

train=True,

download=True,

transform=torchvision.transforms.Compose(

[

torchvision.transforms.ToTensor(),

torchvision.transforms.Normalize((0.1307,), (0.3081,)),

]

),

),

batch_size=batch_size_train,

shuffle=True,

)

test_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

torchvision.datasets.MNIST(

"files/",

train=False,

download=False,

transform=torchvision.transforms.Compose(

[

torchvision.transforms.ToTensor(),

torchvision.transforms.Normalize((0.1307,), (0.3081,)),

]

),

),

batch_size=batch_size_test,

shuffle=True,

)

Next, we’ll declare a model with LSTM as the input layer and Dense as the logit layer.

# Recurrent neural network (many-to-one)

class Net(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, hidden_size, num_layers, num_classes):

super(Net, self).__init__()

self.hidden_size = hidden_size

self.num_layers = num_layers

self.lstm = nn.LSTM(input_size, hidden_size, num_layers, batch_first=True)

self.fc = nn.Linear(hidden_size, num_classes)

def forward(self, x):

# Set initial hidden and cell states

h0 = torch.zeros(self.num_layers, x.size(0), self.hidden_size).to(device)

c0 = torch.zeros(self.num_layers, x.size(0), self.hidden_size).to(device)

# Forward propagate LSTM

out, _ = self.lstm(

x, (h0, c0)

) # out: tensor of shape (batch_size, seq_length, hidden_size)

# Decode the hidden state of the last time step

out = self.fc(out[:, -1, :])

return out

# Instantiate the model with hyperparameters

model = Net(input_size, hidden_size, num_layers, num_classes).to(device)

# Loss and optimizer

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

Now, we’ll define the training loop in which gradient calculation and optimizer steps will be defined. Here we’ll also define our clipping instructions.

# Train the model

total_step = len(train_loader)

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for i, (images, labels) in enumerate(train_loader):

images = images.reshape(-1, sequence_length, input_size).to(device)

labels = labels.to(device)

# Forward pass

outputs = model(images)

loss = criterion(outputs, labels)

# Backward and optimize

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

# Gradient Norm Clipping

#nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), max_norm=2.0, norm_type=2)

#Gradient Value Clipping

nn.utils.clip_grad_value_(model.parameters(), clip_value=1.0)

optimizer.step()

run['training/train/loss'].append(loss)

if (i+1) % 100 == 0:

print ('Epoch [{}/{}], Step [{}/{}], Loss: {:.4f}'

.format(epoch+1, num_epochs, i+1, total_step, loss.item()))

run.stop()

Since PyTorch saves the gradients in the parameter name itself (a.grad), we can pass the model parameters directly to the clipping instruction. Line 17 describes how you can apply clip-by-value using PyTorch’s clip_grad_value_ function.

To apply Clip-by-Norm, you can change this line to:

# Gradient Norm Clipping

nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), max_norm=2.0, norm_type=2)

You can see the above metrics visualized in my Neptune project.

So, up to this point, you understand what clipping does and how to implement it. Now, in this section, we’ll see it in action, sort of a before-and-after scenario to get you to understand the importance of it.

The framework of choice for this will be PyTorch since it has features to calculate norms on the fly and store it in variables.

Let’s start with the usual imports and dependencies.

import time

from tqdm import tqdm

import numpy as np

from sklearn.datasets import make_regression

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

import torch.optim as optim

from torchvision import datasets, transforms

import neptune

run = neptune.init_run(project=project_name, api_token=api_token)

For the sake of keeping the norms small, we’ll only define two linear or dense layers for our neural network.

class Net(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(Net, self).__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(20, 25)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(25, 1)

self.ordered_layers = [self.fc1, self.fc2]

def forward(self, x):

x = F.relu(self.fc1(x))

outputs = self.fc2(x)

return outputs

We created the ordered_layers variable in order to loop over them to extract norms.

def train_model(model, criterion, optimizer, num_epochs, with_clip=True):

since = time.time()

dataset_size = 1000

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

print("Epoch {}/{}".format(epoch, num_epochs))

print("-" * 10)

time.sleep(0.1)

model.train() # Set model to training mode

running_loss = 0.0

batch_norm = []

# Iterate over data.

for idx, (inputs, label) in enumerate(tqdm(train_loader)):

inputs = inputs.to(device)

# zero the parameter gradients

optimizer.zero_grad()

# forward

logits = model(inputs)

loss = criterion(logits, label)

# backward

loss.backward()

# Gradient Value Clipping

if with_clip:

nn.utils.clip_grad_value_(model.parameters(), clip_value=1.0)

# calculate gradient norms

for layer in model.ordered_layers:

norm_grad = layer.weight.grad.norm()

batch_norm.append(norm_grad.numpy())

optimizer.step()

# statistics

running_loss += loss.item() * inputs.size(0)

epoch_loss = running_loss / dataset_size

if with_clip:

run["training/train/grad_clipped"].append(np.mean(batch_norm))

else:

run["training/train/grad_nonclipped"].append(np.mean(batch_norm))

print("Train Loss: {:.4f}".format(epoch_loss))

print()

time_elapsed = time.time() - since

print(

"Training complete in {:.0f}m {:.0f}s".format(

time_elapsed // 60, time_elapsed % 60

)

)

This is a basic training function housing the main event loop, which contains gradient calculations and optimizer steps. Here, we extract norms from the said ordered_layers variable. Now, we only have to initialize the model and call this function.

def init_weights(m):

if type(m) == nn.Linear:

torch.nn.init.xavier_uniform(m.weight)

m.bias.data.fill_(0.01)

if __name__ == "__main__":

device = torch.device("cpu")

# prepare data

X, y = make_regression(n_samples=1000, n_features=20, noise=0.1, random_state=1)

X = torch.Tensor(X)

y = torch.Tensor(y)

dataset = torch.utils.data.TensorDataset(X, y)

train_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

dataset=dataset, batch_size=128, shuffle=True

)

model = Net().to(device)

model.apply(init_weights)

optimizer = optim.SGD(model.parameters(), lr=0.07, momentum=0.8)

criterion = nn.MSELoss()

for v in [True, False]:

norms = train_model(

model=model,

criterion=criterion,

optimizer=optimizer,

num_epochs=50,

with_clip=v,

)

run.stop()This will create a chart for the metrics you specified, which will look something like this:

You’ve reached the end!

Congratulations! You’ve successfully understood the Gradient Clipping Methods, the problem they solve, and the Exploding Gradient Problem.

Below are a few endnotes and future research things for you to follow through on.

Logging is king!

Whenever you work on a big project with a large network, make sure that you are thorough with your logging procedures.

Exploding gradients can only be efficiently caught if you are logging and monitoring properly.

You can use your current logging mechanisms in Tensorboard to visualize and monitor other metrics in Neptune’s dashboard. What you have to do is simply install neptune-client to accomplish that. Head over here to explore the documentation.

That’s it for now, stay tuned for more! Adios!